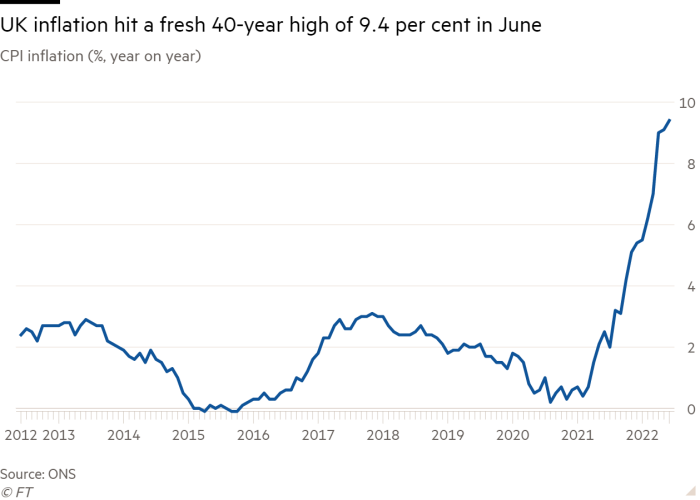

The rate of UK inflation rose to a fresh 40-year high of 9.4 per cent in June as sharp rises in food and petrol prices drove the rate towards double digits for the first time since 1982.

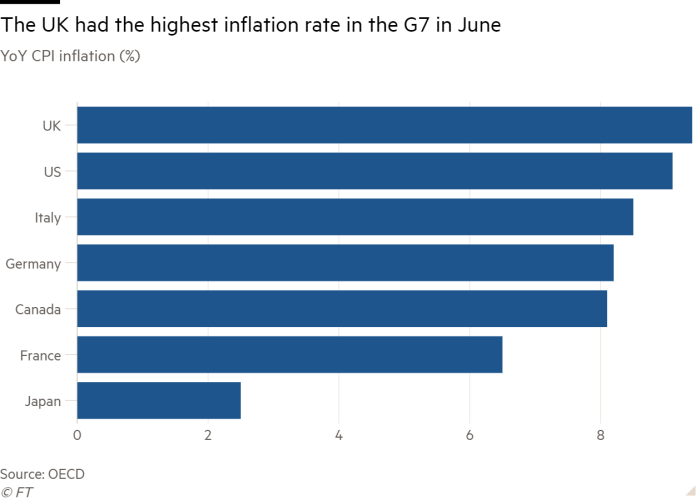

The UK’s rate was again the highest among the G7 group of large advanced economies even before recent wholesale rises in energy prices are reflected in the inflation measure in October.

The June rate was up from a 9.1 per cent rate in May and higher than the 9.3 per cent figure economists had expected.

The figure will intensify pressure on the Bank of England for a forceful response. Nadhim Zahawi, the new chancellor, said on Wednesday he was “working alongside” the Bank to “bear down” on inflation.

Andrew Bailey, governor of the central bank, said on Tuesday that a 0.5 percentage point interest rate rise was “on the table” for its next meeting in just over two weeks’ time.

The BoE is worried that inflation rates well above its 2 per cent target will become embedded in corporate pricing policies and wage rises over the months ahead.

Pipeline inflation pressures were also highlighted by the ONS, with the rate of inflation of manufactured goods leaving factories rising to a 45-year high of 16.5 per cent in June.

The Office for National Statistics said that the main driver of higher annual inflation in June was petrol prices rising by 18.1 pence per litre, the largest rise since equivalent records began in 1990.

Food prices rose 9.8 per cent in the year to June, the highest rate in this category since 2009. The cost of food increased by 1.2 per cent in the month of June alone. There was a similarly large monthly rise in the price of restaurant meals, with the annual rate increasing to 8.6 per cent.

These price rises outweighed downward forces on inflation from second-hand cars and audiovisual equipment.

In the detailed categories, only 6 per cent of the 277 categories checked by the ONS had seen price reductions over the past year and only 29 per cent of categories were rising in price by an annual rate less than 4 per cent, still double the BoE’s inflation target.

Yael Selfin, chief UK economist at KPMG, said that “with further energy bill increases due to take effect from October, the peak in inflation is still some way off, and is not expected to return to the 2 per cent target before mid-2024”.

But some economists drew some comfort from evidence that price rises were increasingly concentrated in food, energy and fuel, suggesting that even though inflation had further to rise, it was no longer spreading much more widely through the economy.

Samuel Tombs, UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, said that although inflation was set to peak at nearly 12 per cent in October, “core inflation . . . will remain on a downward path, easing to about 5 per cent by year-end and to around 2 per cent or so in one year’s time”.

The peak of inflation, coming with the next rise in the energy price cap in October, will put increasing strains on households’ cost of living, even after the government’s support package of a £400 discount to gas and electricity bills and £650 for households receiving means-tested benefits such as universal credit and pension credit.

Jamie O’Halloran, an economist at Pro Bono Economics, an organisation helping the charitable sector, said poorer families were under severe pressure with bills even if they were working.

“This stifling pay squeeze is fuelling spiralling demand for charities’ services,” he said. “Charities and the people they support face little respite from the mounting pressure.”